Exploring children’s experiences of online harms

Our tracker survey provides children and parents with a list of online harms and asks which (if any), they or their children have experienced.

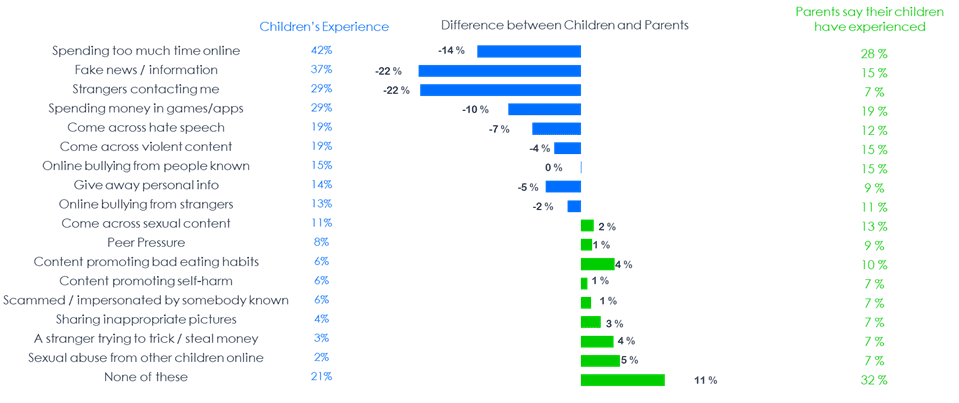

In the chart below, we see the list of online harms and how parents and children report children experiencing them. We’ve then highlighted the difference between those scores.

We will explore some of the hypotheses around why there has been a significant under-estimation of the negative experiences of children and young people online (indicated by the blue bars with minus scores) in the examples below. This under-appreciation of the risks that children report experiencing is concerning, as it means that children might not be receiving the support they need from parents in these areas.

Figure 3: List of online harms experienced by children and reported by parents, showing the difference of results between parents and children.

Looking at fake news or information, 37% of children reported experiencing this, whereas only 15% of parents say their children have experienced it. This considerable difference may be explained by a number of hypotheses: that it is a blind spot for parents underestimating the prevalence of fake news during their children’s online time, that it is being over-estimated by children believing the content they see is untrue as it is not what they believe or have previously heard, or it might seem insignificant to the children who have experienced the issue so it never gets discussed with their parents.

More than four times as many children aged 9-16 (29%) report strangers contacting them compared to parents’ reports (7%). A reason for the significant difference might be down to children normalising this experience and not talking about it with their parents, leading to parents underestimating the issue.

Another reason might be around online gaming habits. We know from our data that more than half of 9-16 year olds play online games against other people (54%). These games often have online chat and messaging functions, which parents may be less familiar with and children aren’t informing them when an interaction with someone they don’t know occurs.

There are only a few areas where parents over-report experiences compared to children. There are significant differences in the reporting of sharing inappropriate images (7% reported by parents, 4% children), strangers looking to steal money online (7%, 3%), and sexual abuse or harassment from other children (7%, 2%). These may be low occurring online harms, but some of the most serious. The reason for the over reporting may be explained by parents have greater concerns over these online harms, so over-report the actual occurrence of them. It may be that children don’t fully understand these risks or maybe under-appreciate what they entail. They need further investigation and monitoring to see how they progress and align with other habits children show online.

How confidence might impact children’s ability to stay safe online

We previously discussed the role of confidence in staying safe online and how it could possibly impact young people’s ability to be safe online.

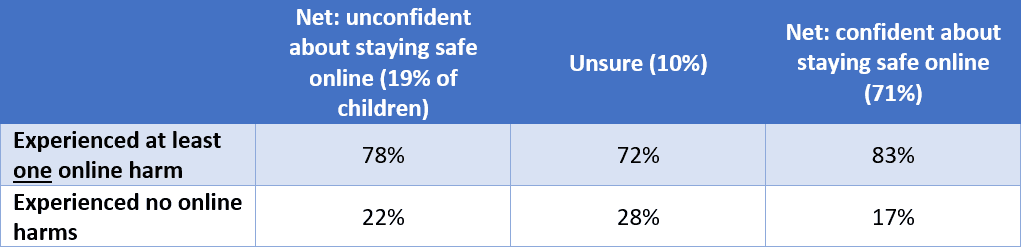

In our analysis we compared children’s reporting of having experienced harm online with their confidence about staying safe online. Our results show that children who say they are confident online are more likely (83%) to say they have experienced harm online – compared to children who are less confident (78%).

So, although a large majority of children say they are confident in staying safe online, they are more likely to report an experience of online harm . This may be down to these children having a better understanding of online issues, so they can more accurately report when the occur. But it may also be due to an over-confidence in the steps needed to be taken to stay safe online.

The lowest group for those reporting online harms are those who are ‘unsure’ whether they know how to stay safe online. This may be because they are also unsure about which online harms they have experienced or the factors that may make up an online harm experience. An interesting group to investigate more into.

Figure 4: Reported experience of online harms by confidence levels of knowing how to stay safe online, by children.

When exploring the background of these groups; 77% of 15-16 years are (net) confident in knowing how to stay safe online compared to 66% of 9-11 year olds – more of the younger group fall into the ‘unsure’ category than being unconfident. Yet amongst 15-16 year olds, 82% have experienced an online harm compared to 73% of 9-11 year olds. This may be explained by having a greater presence online but there does not seem a strong correlation between being confident in knowing how to stay safe online to avoiding online harms.

Online harms can happen to anyone at any time regardless of confidence or capabilities. Where the confidence becomes beneficial is in knowing how to take preventative measures and, when online harms are experienced, knowing how to respond.

A positive outcome is that self-confident children are more likely to take affirmative action when they do come across an online harm, e.g. changing their privacy settings – 22% of ‘confident’ children took this action compared to 16% of ‘unconfident’ children. Whilst those with less confidence were more likely to rely on their friendship network (36%) compared to those with more confidence (27%).