Internet Matters is delighted to participate in this welcome consultation. We have a few introductory comments which frame our thinking before we get into the specific questions. Internet Matters exists to help families benefit from connected technology. We are a not for profit, funded by the internet industry – and we are pleased to bring leading brands together to focus on child safety and digital wellbeing. We provide expert advice to parents, presented in a really usable way, by age of the child, by device, app, or platform or by issue.

We know that engaging with our content gives parents, carers and increasingly professionals the confidence and tools they need to engage with the digital lives of those they care for. Having an engaged adult in a child’s life is the single most important factor in ensuring they are safe online, so providing those adults with the tools, resources, and confidence to act is a fundamental part of digital literacy.

Regulatory basis and complexities for parents

AVMSD stems from the EU body of law which is predicated on an “country of origin” principle. In practice, this means as the consultation document states, the interim regulatory framework will on cover 6 mainstream sites and 2 adult content sites. This will prove very hard to explain to parents who could rightly expect that if the content is viewable in the UK it is regulated in the UK.

While acknowledging the limitations of the AVMSD, the consultation repeatedly notes that to the extent the forthcoming Online Harms legislation will address age-inappropriate content, it will not feel bound to honour the country of origin principle. This is a position we endorse. If the content is viewable in the UK, then it should conform with UK rules.

However, there is a misalignment between the stated aims of the Online Harms White Paper and the scope of the AVMSD. The White Paper speaks largely about platforms which permit the publication of user generated content. The AVMSD is not limited in that way. In this case the AVMSD has got it right. It makes no sense to limit the scope of the Online Harms legislation to platforms which allow user generated content to be published. What matters is the nature of the content, not how or by whom it was produced.

Question 19: What examples are there of effective use and implementation of any of the measures listed in article 28(b)(3) the AVMSD 2018? The measures are terms and conditions, flagging and reporting mechanisms, age verification systems, rating systems, parental control systems, easy-to-access complaints functions, and the provision of media literacy measures and tools. Please provide evidence and specific examples to support your answer.

Our work listening to families informs everything we do – and given we are a key part of delivering digital literacy for parents we wanted to share some insights with you. Parents seek advice about online safety when one of four things happen:

- There is a new device at home

- There is a new app / platform on the device

- Children start secondary school

- There is a safety concern that can be prompted by any number of reasons, not least lived experience, prompts from school, media stories etc.

Parents seek help most often through an online search or asking for help at school. Clearly throughout lockdown, searching for solutions has been more important, meaning evidenced-based advice from credible organisations must be at the top of the rankings.

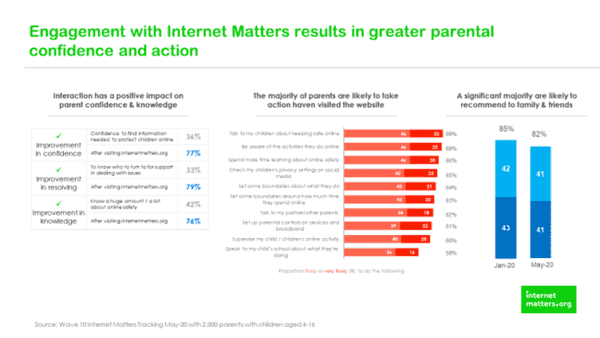

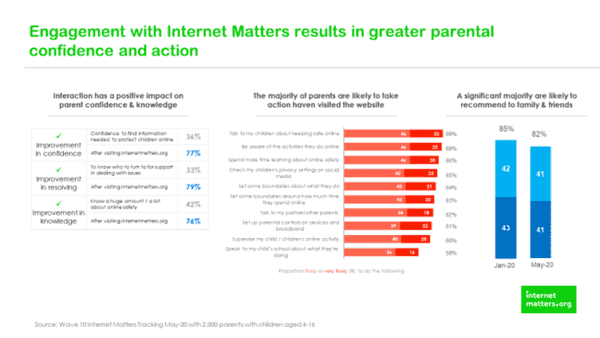

Once parents are engaged with advice it has to be easy to understand – and so we regularly poll parents on what they would think talk and do differently after engaging with our website. The charts below demonstrate that serving parents content that meets their requirements drives meaningful and measurable change.

These data points indicate that digital literacy amongst parents can and is influenced by good quality resources – which equip them to have routine conversations with their children about their digital lives. Moreover, our pages on parental controls consistently rank in the top 10 most popular pages.

Question 20: What examples are there of measures which have fallen short of expectations regarding users’ protection and why? Please provide evidence to support your answer wherever possible.

We have to conclude that moderation of live streaming is not working currently and perhaps cannot work, abuse of platforms terms and conditions happens in real-time. In the following two examples it’s not simply terms and conditions that were abandoned, it was much more serious. The tragic recent suicide was circulated globally within seconds and although platforms took quick and decisive action too many people saw that harrowing content on mainstream apps, with little or no warning as to graphic content. As we all know, this wasn’t the only example of live streaming moderation failure, as the Christchurch shootings highlighted back in March 2019.

Clearly, these are complex issues where someone deliberately sets out to devastate lives through their own actions and their decision to live stream it. Of course, the two examples are not comparable save in what we can learn from them and what a regulator could meaningfully do in these situations. Perhaps it is in the very extreme and exceptional nature of this content than comfort can be found – in that in nearly every other circumstance this content is identified and isolated in the moments between uploading and sharing. Clearly, these are split second decisions which are reliant on outstanding algorithms and qualified human moderators. Perhaps the role of the regulator in this situation is to work with platforms onto which such content can be or was uploaded and viewed and shared to understand and explore what went wrong and then agree concrete actions to ensure it cannot happen again. Perhaps those learnings could be shared by the regulator in a confidential way with other platforms, simply for the purpose of ensuring lessons are learnt as widely as possible – for the protection of the public, and where appropriate for the company to provide redress. For that, to work the culture of the regulator and its approach has to be collaborative and engaging rather than remote and punitive.

Recommendations the Regulator may want to deploy could include (but not be limited to) requesting companies have established plans to work together to ensure notifications are shared immediately across platforms – as there is no commercial advantage in keeping this information within one platform.

The other issue that requires detailed consideration are comments under videos – be that toddlers in paddling pool, or teenagers lip-synching to music videos. Perhaps there are two separate issues here. For the accounts of young people between 13-16, unless and until anonymity on the internet no longer exists, ’platforms should be encouraged take a cautious approach to comments, removing anything that is reported and reinstating once comment has been validated.’

We would encourage the regulator to continue to work with platforms to identify videos that although innocent in nature, attract inappropriate comments and suspend the ability to comment publicly under them Often account holders have no idea who the comments are being left by and context is everything. A peer admiring a dance move, or an item of clothing is materially different from comments from a stranger.

For as long as sites are not required to verify the age of the users, live streams will be both uploaded and watched by children. Children have as much right to emerging technology as anyone else – and have to be able to use it safely. So, the challenge for the regulator becomes how to ensure children who are live streaming can do so without inappropriate contact from strangers.

Whilst many young people tell us they like and appreciate the validation they receive from comments, the solution isn’t to retain the functionality. It’s to stop it and invest the time and money in understanding what is happening in the lives of our young people that the validation of strangers is so meaningful to them.

For parents posting images of toddlers in paddling pools, there are both technical and educational responses. There should be the ability for images to only be seen in private mode so that strangers are not able to comment. Secondly, there should be an educational play to parents – which probably starts with conversations between the expectant mother and the mid-wife about how much of their child’s infant life it is appropriate to post online for the world to see. The regulator could play a role in challenging the show-reel lifestyle that has rapidly become the norm.

Question 21: What indicators of potential harm should Ofcom be aware of as part of its ongoing monitoring and compliance activities on VSP services? Please provide evidence to support your answer wherever possible.

In the last 18 months, Internet Matters has invested significant amounts of time and resource into understanding the online experience of vulnerable children – specifically how it differs to their non-vulnerable peers. Our report Vulnerable Children in a Digital World published in Feb 2019 demonstrated that vulnerable children have a markedly different experience online. Further research demonstrates that children and young people with SEND are at particular risk as they are less able to critically assess contact risks and more likely to believe people are who they say they are. Likewise, care experience children are more at risk of seeing harmful content, particularly around self-harm and suicide content. There are many more examples.

The point here is not the vulnerable young people should have a separate experience if they identify themselves to the platforms, but more than the regulator and platforms recognise that there are millions of vulnerable children in the UK who require additional support to benefit from connected technology. The nature of support will vary but will inevitably include additional and bespoke digital literacy interventions as well as better content moderation to remove dangerous content before it is shared.

Data from the Cybersurvey 2019 by Youthworks in partnership with Internet Matters indicates:

- Young people are increasingly exposed to harmful content talking about suicide or self-harm. In 2019, a quarter of teen respondents had ever seen content talking about suicide and 13% had seen content about self-harm. In 2015, 11% had ever seen content encouraging self-harm or suicide

- The percentage who have experienced racist bullying or aggression personally online in 2019 is higher than in 2015; 13% compared to 4%

- The percentage who have personally experienced homophobic bullying or aggression online in 2019 is almost four times as high as in 2015; 15% compared to 4%

- Content risk is more commonly experienced than contact risk:

- Pro-anorexia content, which we have flagged in several earlier Cybersurvey reports, is joined this year by content encouraging teens to ‘bulk up your body’. This is widely seen, mostly by boys. (While fitness is positive, bulking up may be harmful if, to achieve this, a young person is encouraged to use substances which may not be as labelled)

Content about self-harm is seen ‘often’ by already vulnerable teens, especially those with an eating disorder (23%) or speech difficulties (29%), whereas only 9% of young people without vulnerabilities have ‘ever’ seen it and only 2% have ‘often’ done so.

Question 22: The AVMSD 2018 requires VSPs to take appropriate measures to protect minors from content which ‘may impair their physical, mental or moral development’. Which types of content do you consider relevant under this? Which measures do you consider most appropriate to protect minors? Please provide evidence to support your answer wherever possible, including any age-related considerations.

In addition to the self-harm and suicide content detailed in our answer to question 21, there are several other types of content that can impair children’s physical, mental or moral development which includes (and isn’t limited to)

- Pornography and all other adult and sexualised content that surround pornography. This also includes the impact this content has on children’s perceptions of healthy relationships, consent and the role of women. Our report – We need to talk about Pornography details these issues in the context of parental support for age verification

- Violence – the normalisation of violence and the implications of content around certain types of music and gang culture can be highly damaging

- Criminal activity – from the use of VSP to recruit minors for county lines and the glorification of glamourous lifestyles there is a range of harmful content that encourages criminality

- Gambling, smoking and alcohol, knives – children should not be able to gamble online – it’s illegal offline and should be both illegal and impossible online. Likewise, there are age restrictions on the sale of restricted items; tobacco, alcohol and weapons and this should mean it is impossible for children to review this content in the form of an advert that glamourises it or be presented with an opportunity to purchase it

- Ideology / Radicalisation / Extremism – Whilst we would not seek to limit freedom of speech, children and young people merit special protections so that they are not subject to radical and extreme ideology and content

Perhaps the way to consider this is by reviewing and updating the content categories the Internet Service Providers use for blocking content through the parental control filters. All user-generated content should be subject to the same restrictions for children. What matters to the health and wellbeing of children is the content itself, not whether the content was created by a mainstream broadcaster or someone down the road.

What measures are most appropriate to protect minors?

- Restricted, some content should just not be served to some audiences

- Greater use of splash screen warnings to identify legal but harmful content

- More draconian actions against users that create content that breaks platforms terms and conditions

- Age verification for adult content and age assurance for users aged 13-16

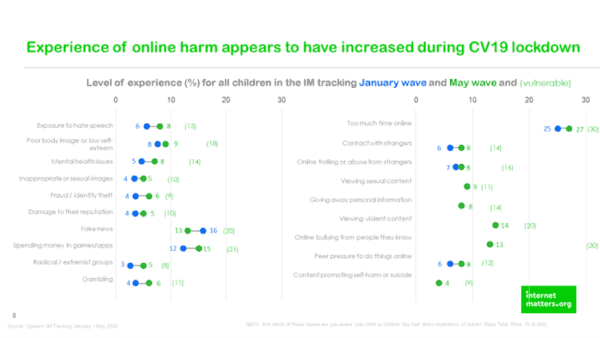

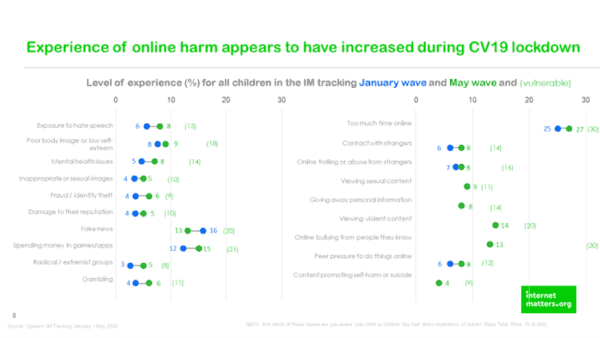

There is an urgency to this as our data shows that experiences of online harm have increased during lockdown.

Question 23: What challenges might VSP providers face in the practical and proportionate adoption of measures that Ofcom should be aware of? We would be particularly interested in your reasoning of the factors relevant to the assessment of practicality and proportionality.

It may be useful to draw a distinction here between illegal content, where there are very clear requirements and legal but harmful content, where there is a world of confusion

This is a serious and complex problem which will require significant work between the platforms and the regulator to resolve. Given the Government is minded to appoint Ofcom to be the Online Harms Regulator there will be as much interest in how this is done as in that it is done. Precedents will we set, and expectations created.

Question 24: How should VSPs balance their users’ rights to freedom of expression, and what metrics should they use to monitor this? What role do you see for a regulator?

- Clarity on community guidelines on what is appropriate and not and what will be acceptable / tolerated. Abuse it and you’re off. Freedom of expression is not curtailed because you could find another platform to express those views – but they are not acceptable on this one

- Metrics – prevalence, takedowns and reporting

- Regulator role is to ensure community standards are being enforced, recognise that as with all rules people will push them and evade them, so an element of human moderation and common sense also required

- Regulator needs to recognise that education is a key part of this too, so VSPs that invest in independent education programmes that enhance digital literacy should be encouraged/ looked on favourably/given a levy discount

Question 25: How should VSPs provide for an out of court redress mechanism for the impartial settlement of disputes between users and VSP providers? (see paragraph 2.32 and Article 28(b)(7) in annexe 5). Please provide evidence or analysis to support your answer wherever possible, including consideration on how this requirement could be met in an effective and proportionate way.

Internet Matters has no comment on this question

Question 26: How might Ofcom best support VSPs to continue to innovate to keep users safe?

- Recognise off app investments and interventions in media / digital literacy that can demonstrate impact through robust evaluation

- Ensure they recognise that compliance is more than content removal – as in the Irish model, it has to include measures to minimise the spread and amplification of harmful content

- Be clear about the intention of the requirements – where, again as per the Irish model, there is a cycle of harm minimisation whereby the numbers of people exposed to harmful content is meaningfully reduced over time as a direct result of the measures taken

- Make reporting of concerning content as easy as uploading content and keep reporters aware of processes and likely resolution timescales. This should include clearly published response times that meet a minimum standard and keep users informed. Additionally, we suspect that some of the wording around reporting content is off-putting for children, so suggest some work is done to identify the most appropriate wording and process for young people so that they are more likely to flag this content. Additionally, there needs to be a sustained effort on the part of the platforms to restore confidence in their reporting mechanisms so that users of all ages believe that something will happen if they make a report

- Make reporting easy for minors – so test with them the most appropriate way to do that by the platform. Is complex, specific language best for young people, or would softer language like “I don’t like this” or “this content makes me unhappy” be more effective? Additionally, prioritise their concerns and perhaps trial what happens if reports from minors are removed and then examined and reinstated if required. If we really wanted to make the internet a safe place for children, we would focus on their needs – on the platforms they are likely to frequent

Question 27: How can Ofcom best support businesses to comply with the new requirements?

- Recognise the limitations in the scope and timing of the requirements – and message them accordingly. If the regulations only apply to 6 or 8 organisations, don’t overclaim – they will not be world-leading. This is important so that parents are realistic about what changes the requirements will bring about and will not become less vigilant because they believe there is a regulated solution

- Recognise that size is not a pre-requisite for the existence of risk and harm, and that in every other consumer product domain business cannot put less safe or more risky products on the market because they are small. Micro-breweries have the same legal requirement to comply with all appropriate health and safety regulations as Coca-Cola. It’s the same for toy manufactures and film producers. The right to be safe, or in this case is not harmed is absolute and not dependent on the size of the organisation you are consuming a product or service from

Question 28: Do you have any views on the set of principles set out in paragraph 2.49 (protection and assurance, freedom of expression, adaptability over time, transparency, robust enforcement, independence and proportionality), and balancing the tensions that may sometimes occur between them?

- Irish proposals recognise this is an iterative process, so welcome sentiments to be agile and innovative. The focus of regulation in compliance with codes, rather than personal behaviour – but still need a place to educate so that behaviour is addressed. The Law Commission’s current consultation on online crimes is also an interesting intervention here as such changes to the law will create legal and therefore cultural clarity around what is acceptable and legal behaviour online

- Freedom of speech and expression concerns can be addressed through terms and conditions – so there may be a place where your extreme views are welcome – but this isn’t the appropriate platform for that. Not suggesting you can’t express those views but simply stating you cannot do that on this platform

- Recognition of the challenges of age verification for minors and margins of error in age assurance and the inevitable limitations of those technologies